We interview What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? ‘s director, Roberto Minervini, about identity, freedom and his “brutally honest” way of establishing trust in relationships.

When we approached Roberto Minervini to interview him on his latest project, little did we know that his What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? would turn out to be the winner of the Grieson Award for Best Documentary at this year’s BFI London Film Festival. What we did know, however, is that his meditation on the state of race in America is unlike any other film we’ve ever seen. First with his award-winning Texas trilogy (The Passage, 2011; Low Tide, 2012; Stop the Pounding Heart, 2013) and then with his analysis of violence, war and drug addiction in Louisiana (The Other World, 2015), the acclaimed Italian director has developed his own way of uncovering a series of important issues affecting the broken country in which he has been living for over ten years, and his latest film is no exception.

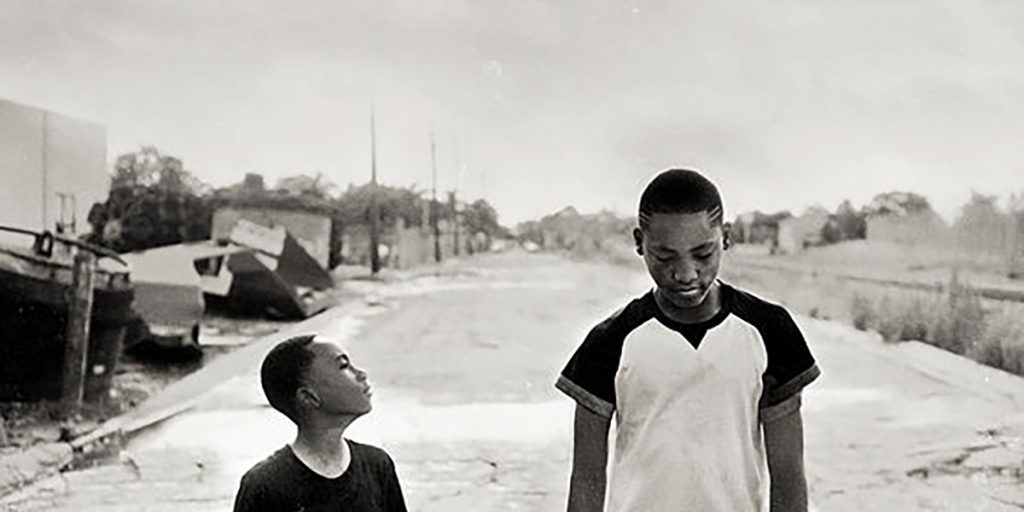

In What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire?, we are introduced to the exceptional New Orleans “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” bar owner Judy Hill and her family, but we also meet Chief Kevin of the Mardi Gras Indians, young but wise brothers Ronaldo and Titus and the representatives from the New Black Panther Party for Self Defense. The characters we see belong to four different communities, but Minervini shows them to us with such honesty and empathy that we soon understand that the struggles they face are very similar and very real. The director’s involvement is not limited to observing the subjects of his documentary through a lens: he spends time with them and establishes a relationship whose roots can be grasped even in the few moments he shows us on the screen.

Your films seem to belong to a genre of their own that has sometimes been categorised as both documentary and drama. Can you tell us about your creative process?

Roberto Minervini: I think being selective is one of the key words of what I’m trying to do, because my work is not one of pure, straightforward observation. I am very selective of what I can observe, and that has an impact on the aesthetic of the film. If we were to film right now… You and I are talking in a room with very flat lighting coming from the ceiling, and if this were to be a very important moment that I wanted to film and those were the lighting conditions, I would not film it. I would be hoping, trusting that a moment like this or of similar intensity would just present itself at another time, or maybe never again, but it’s very important to have rigour in the way you use the aesthetics of the light.

The form and the montage I employ are employed because of the added element of fiction, as that is the language most commonly spoken. More than a filmmaker, sometimes I’m an intermediary: I’m almost a translator of what I see. Really, per se, any moment could be misunderstood, but, since I’m a communicator and a translator, I’m to find a better way – the best way – to make sure that the film communicates something to the audience. My cure, my attention to form and my way of re-writing the story through editing and montage are essential to my way of making films.

What you said about not filming a situation when the conditions aren’t right and trusting that the same situation would present itself again in the future is really interesting.

Roberto Minervini: It’s my attitude to work. If I want to make films like this, where we spend months and months filming together, an important prerogative is that we need to be ready – me and my crew – to let go of control. I don’t complain if the camera was off and we thought we were filming, I don’t complain if a memory card is lost or if the sound doesn’t work. I never complain: it happens all the time, and it’s part of the process. Why am I saying that the moment might present itself at another time? The foundation to all that is that making the film is absolutely secondary to experiencing what’s going on. We are experiencing what we are, what me and the characters were going through together, no matter whether we were filming or not.

Knowledge and relationships are experiential so, in that sense, when we experience something together, that is not a point of arrival: it’s a point of departure. Something else will form from this experience and maybe at that time we will be filming it. Take the music scene. Many times, for practical reasons – because I wasn’t up for it or maybe emotionally not there… we didn’t film it. And then, one time, it just happened, and it happened to be such an emotional moment because the performance was heavily affected by the fact that Judy was losing the bar: that’s how it happened. All my films have many examples of this, and the foundation is that filming something is absolutely secondary to living it.

You talked about being a translator, living the moment and experiencing these moments. When you start shooting a film, do you know what the final product is going to look like?

Roberto Minervini: No, I never ever do. I never wrote anything for this film, or for the two films before this. I have never written a single word, I don’t review footage, I don’t even take a look at a single clip: the editors look at the footage before I do. The editor lives in Belgium, so, when she comes to me and talks to me about the film, she has seen the footage, while I speak based on memory and on my experience. I keep the experiential realm “at the top” for as long as I can, compared with the filmmaker I am. Every time we discuss the film, until we are really ready to cut, it’s all based on my experience.

I find this very helpful, because the film has to reflect an experience: it doesn’t have to reflect a preconceived notion of a story, which means absolutely nothing to me. When we are editing, I’ve never seen the footage: I am “based” on my very fallacious memory – by the way, I don’t remember much! (laughs) It’s how it is, and in this case I have 150 hours of footage, but I remember the experience, and that’s the beauty of editing. I felt the backstory, so as an editor I’m much more than just writing or editing notes.

How do you get your characters to share all these personal things with us?

Roberto Minervini: There’s a relationship: we’ve been hanging out for a long time. Like everything else in life, and like with every other relationship, there are bonding moments, like… when you fall in love: there’s always a moment in which you look at each other in the eyes for too long. There’s always something, and there have been many instances when we bonded. The kids (Ronaldo an Titus) were probably friends with my kids before they were friends with me. Many times we’ve been shooting together and we’ve been in situations where all of us really had to hold each other’s hands and help out, from Judy all the way to my collaborators. There have been many experiences that really made us develop trust: trust and intimacy are nothing more than being able to be yourself, knowing that you won’t be judged or hurt. When you let go of fear, you feel intimate and you trust people. It all starts from me: I’m very open, brutally honest and transparent. I know these people as much as they know me, despite the fact that they’ve never filmed me with a camera, but at that point the camera doesn’t change much.

The Black Panthers aren’t exactly well-known for being so open to being filmed…

Roberto Minervini: No, never! (laughs) They denied participation in white-controlled media for decades! Krystal Muhammad, the Chair of the Black Panthers, called this decision a spiritual one. It comes to myself and the Panthers being behind closed doors, with them trying to figure out who I was and what I was doing, and me just being honest. It all goes back to the result: I’m never pitching a project, and if they don’t want to participate… I totally understand, that’s ok. Many times I’ve lost characters all of a sudden, but everyone you lose is also an opportunity for somebody new (to arrive). I’m open and I’m not doing it thinking about the participation. It was me once who didn’t want to work with them because I was scared: I didn’t want to “step into the dark side”. But then I realised that I was scared just because, as a white guy, I had a choice – whether to be there or somewhere else. And then I thought – ok, that’s enough reason for me to accept participating.

I genuinely, deeply don’t care about the end result of our films: those experiences will stick with me forever. In those 150 hours of footage, there are moments concerning myself and the characters that are so intimate and so private that I never showed them on film. Perhaps some of those moments would be way better than what I did screen, and would probably receive more praise, but those were part of us and had nothing to do with the film.

What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire is a film about race in a country which is essentially broken, and we can very much feel this message throughout the film, but the stories you show us are so personal that I also felt a strong sense of community.

Roberto Minervini: I think what you’re saying is true. In order to keep the sense of community and of collective identity alive, you have to keep historical memory, so that memory can live. It’s no coincidence that these people struggle: sometimes we – as white, privileged people – think “oh, in the third world they’re happy to dance”. But that is not happiness: that is actually the resilience of keeping traditions, and therefore legacies, alive. That is the definition of identity: identity doesn’t die, resilience doesn’t die, the sense of community doesn’t die. That’s what powers do to erase a minority: when you try to eliminate an opponent, you try to erode its collective identity. That’s why a lot of people are not allowed to practice their religion, as, if you attack their religion, you’re attacking their core, their values and their own history.

At the beginning and at the end of my film, you can observe black people together with the Mardi Gras Indians, because, after slavery, they kind of bonded to a similar fate. Why does the film begin and end with that? Because these people are still symbolically claiming their territories, at night, when nobody sees them, as to say: “We’re still here. We’re still brandishing these swords, we’re still chanting in our own jargon, we’re still wearing what we want to wear. We are free: you cannot take that away even if you push us underground, in the dark alleys of history”. That’s how the film begins and ends, and that’s really what the film is about, but it’s not my history: it’s their own. No matter what happens in the middle, the sense of identity and legacy stays alive, because the community will never die.